61. No One Gets to Tell Anyone They're Tasting Beer Wrong, Actually

Addressing gatekeeping in language around beer, wine, and hard seltzer; plus tarot to be careful what you wish for (but do wish for a DDH Citra IPA).

What We’re Really Saying When We Say, “You Can’t Say That” About Beer (or Wine, or Hard Seltzer)

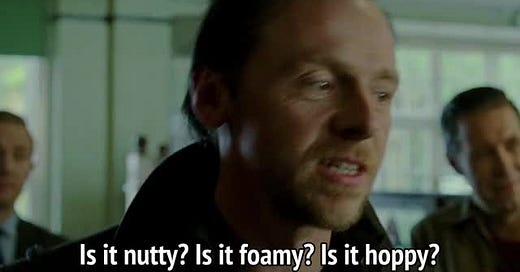

It seems like every few months someone thinks (incorrectly) that the world desperately needs to hear his (because let’s be honest, it’s probably an older white dude) opinion on some beer descriptor, and will log on to Twitter-dot-com to fire off some embarrassingly overzealous judgment on the word in question. It’s one of the gross but stubborn elements of craft beer culture that seems like it will just carry on until we’re all on our deathbeds wishing we didn’t waste so much goddamned time on arguing about adjectives.

Except: sometimes, and in some ways, these adjectives matter. I’ve developed an eye-twitch response to these kinds of tweets and decrees because it really gets my goat that anyone thinks they should be some kind of gatekeeper, deciding anyone else’s perception of a beer, and expression of that perception, is wrong. Any person should be able to use whatever word resonates with them, that helps them make sense of that beer, that connects that beer to their own experiences. We should all just be happy people are trying new beers and actually taking the time to really understand them. To me, when you tell someone the terms they’re using to describe a beer are wrong, you’re telling them that they don’t have the experiences or the memories or the palates for that beer, that that beer is not for them. And that can and often does translate into some kind of culturally biased barrier. We know better in the year of our lord Beelzebub that the craft beer industry has failed at welcoming anyone not white all these years and that we need to be changing that, and yet, we’re still wringing our hands over whether certain words should be allowed to describe certain beers.

“There is a story of a somm who was taking his classes, and when he mentioned that he smells notes of papaya, the classroom laughed at him because it was not on the quote-unquote ‘aroma wheel,’” Miroki Tong tells me. I spoke to the Toronto-based wine blogger because not only does this issue of language affect wine, too, and every other beverage (and thing in the world, really), but also because Miroki specifically speaks about and works toward opening language and access up in wine (and has dealt with trolls on Twitter in the process). Miroki points out that not only does this kind of designating certain language as “right” and “wrong” fly in the face of the fact that perceiving wine (or beer) is all subjective, and not only does it tell a person that this is not for them, but it also creates and maintains this idea that because certain people with certain reference points can’t “correctly” taste this drink, they can’t enter the industry either. A little judgment over a little word can go a long way in hindering inclusion, and perpetuating whiteness in worlds like wine and craft beer.

“There are tons of adjectives and beer flavors that we use that aren’t accessible, or are highly Westernized versions of what we intend to be educational, but this isn’t how beer is consumed,” beer journalist and marketer Samer Khudairi told me in a Twitter DM chat weeks ago when I first started putting this newsletter issue together. In the meantime, quite fortuitously for this conversation, Good Beer Hunting published a really great and intriguing read from author Mark Dredge, who created his own influential beer flavor wheel in 2012. What I appreciate about Dredge is that he did not create that wheel, sit back, cross his arms, and prepare to defend it staunchly for the rest of his life, telling people who find different flavors they’re wrong. He’s updated the wheel, and written stories like this GBH piece, where he wonders:

“Had I just produced something which reinforced Western ideas of flavor language? Was this actually a useful, global tool inclusive of a broad range of drinkers? Were those words common and relatable to a lot of people? And if not, how could they be made more relatable?”

This brings up a crucial point to understand here: it’s not that the adjectives we use to describe beer styles are wrong. Not even in their Eurocentric-ness, if the beer was created in Europe. It’s not wrong to use terms relatable to Belgian, German, and British reference points for beers born in Belgium, Germany, or England. What we need is a bridge between these terms and other reference points in other cultures. We need wildly improved accessibility. We need open-mindedness and flexibility, even in teaching and maintaining what makes a Belgian dubbel a Belgian dubbel.

“I’m a Certified Cicerone and I had to learn a lot of things I wasn’t familiar with studying for the exam, and I think there’s something really wonderful in learning terminology and things from other cultures,” Dr. J Nikol Jackson-Beckham tells me in a phone call. Dr. J is, of course, an incredible source for this topic, since not only is she experienced within craft beer, a DEI consultant (Crafted for All), educator, and nonprofit founder (Craft x EDU), but she is also a former professor of Communication Studies. (Dr. J also chatted about this topic with David Nilsen for his podcast Bean to Barstool, highly recommend!) Dr. J calls these learning opportunities powerful, saying they can help you travel different places conceptually. Offering that to someone openly when you’re teaching about beer, she says, can be wonderfully collaborative.

But so it is therefore the way we communicate these terms and frame them in this educational context. Is language being presented as this linguistic kind of travel, connecting different cultures? If you tell someone from Japan that a British brown ale has biscuity notes, are you making sure you are relating that to something that would strike familiarity for them? In the GBH piece, Dredge interviews the great Garrett Oliver, who describes how he does this in his teaching around the world:

“‘If I’m talking about a burnt sugar character, in one context I will talk about the burned surface of a crème brûlée, in another context I’ll talk about the syrup on top of a flan,’ he says, while in the U.K., ‘I might refer to the darker versions of Lyle’s syrup, but if you mention Lyle’s in the United States, no one’s ever heard of those.’”

It’s when you don’t do this, and worse, when you use these terms with the intention of being exclusive, Dr. J says, that there’s a problem, adding that it’s not necessarily always maliciousness, but a lack of care. Often, and I think it’s easy to sense when this is happening, people draw these hard and fast rules around descriptors as ways to prove their own expertise and establish themselves as authorities (they think that’s what they’re doing, anyway). It’s probably frequently more of a self-centered thing, to attempt to validate their own knowledge, rather than to intentionally exclude others—but the consequence of that exclusion remains.

“If we utilize [language] to close doors or be elitist or play power games where we show ourselves to be ‘more knowledgeable’…that’s where it’s almost like the lexicon gets passively weaponized, right?” Dr. J points out. “I think the important piece is to not necessarily just give it up because it’s problematic but use it to be invitational rather than using it as a way to kind of will your own personal power, privilege, and space.”

“I have a friend, she’s Chinese, and she kept telling me how she doesn’t really talk about wine very much amongst our circle of friends who are all winos because she doesn’t think she knows very much about wine,” Miroki tells me. “I was talking to her about the tasting experience and she kind of looked at me and then said, ‘I wonder if that’s why I don’t really comfortable talking about wine, because I don’t know a lot of these flavors people are talking about. I don’t really eat blackberries or blueberries, that wasn’t a food staple growing up. I don’t feel comfortable because I feel like if I say something else, it will be incorrect.’ I remember looking her in the eyes and being like, ‘No, you’re not incorrect. We just all use these notes because this is the sort of vocabulary based on my experience, or what my education is, or sometimes what’s coming to my head quickly—but that doesn’t mean what that is for you is incorrect.’ I think a lot of people have been conditioned to believe if they say something other than what ‘the expert’ is saying, it’s incorrect. And that’s not true.”

Taking valid terms that capture the essence of a beer or wine well and deciding they’re the only “correct” terms instead of using them as jumping-off points for interpretation and expansion cuts entire cultures out of the conversation and keeps beverage alcohol small, narrow, homogeneous, exclusive. It tells consumers they won’t like this because they won’t get it, which, as Miroki points out, is just bad business—it obviously behooves any brand to connect with as many people as possible. It tells people that they could never be sommeliers or brewers. It others the brands that do exist, based on rigid Westernized constructs.

Think about the language that exists to differentiate styles, for education, for organization, for communication to consumers. Again, this language is not wrong, it’s just got to be opened up and made flexible for translation and access. As Dr. J, who has judged beer competitions, points out, judges need common language for comparative analysis. What are they all measuring the entered beers against? But, for one thing, why, she asks, would we ever expect consumers to be operating at that level of analysis? She uses the example of a regular car owner taking their car to a mechanic, who then diagnoses the problem and delivers the news—in terms an average car owner would understand, not in terms a fellow mechanic would. “In beer, it’s like we do the opposite,” Dr. J says. If we start by opening this language up so anyone can find their own ways in, then maybe they stay an enthusiastic consumer for life, or maybe they feel welcomed to an education in beer or wine and start interpreting and discussing descriptors until the common language in a competition makes sense and they, too, can be judges.

For another thing, the language that shapes competition categories could use an overhaul in inclusivity. What are competitions actually considering fit to enter? It’s fine to have categories for Eurocentric beer that then use Eurocentric language for analysis, but are other beer styles from other parts of the world also included, with corresponding language?

Hard seltzer is a segment of beverage alcohol where I didn’t think this issue would exist. It’s so new compared to beer and wine, and it’s a very simple format of taking seltzer and adding any flavors, so why and how would there be rules about what flavors from where fit into the “right” box? But biases and gatekeeping have managed to creep into this seemingly wide open space, Lunar co-founder Kevin Wong tells me. I know from working with Lunar a bit for TapRm content that their craft seltzers are lovely expressions of real Asian fruits sourced from Asian countries that grow them, like yuzu, lychee, and plum, and Kevin and his co-founder Sean Ro built the brand to fill this void for alcoholic beverages here in America that do in fact feature Asian ingredients and that can be paired with Asian dishes.

Kevin says he was looking at the submission process for the U.S. Open Hard Seltzer Championship. The categories were “very limiting, like ‘cherry’ or ‘raspberry,’ or very broad, like ‘anything goes’ or ‘fruit.’ We were like, ‘How do we submit Lunar? Where does lychee belong? Why isn’t there a ‘citrus’ category? Do I submit all our flavors to ‘fruit’ or ‘anything goes?’ But then I’d just be competing with myself.” Kevin also wondered why there was no transparency as to the judges and their backgrounds. “For a competition like this one where it’s for such a modern category with global appeal, I’d hope there is diversity on the tasting panel—across types of somms, gender, background.”

“From a more meta/societal perspective, this inability to figure out where our flavors belong isn’t a new feeling for people like me who identify with multiple cultures,” Kevin adds. “Do I belong in America? Do I belong in Asia?”

“Competitions limited to a Western lens can make it harder for companies like Lunar to compete and win accolades, which can be useful tools for attracting new customers and media attention,” points out Stasia Brewczynski, a food and drinks writer who is also an account manager at District One Studios, where she works with Lunar. Kevin says this boxes Lunar and brands like it out at step one, creating a lack of opportunities for visibility, which is then a self-perpetuating cycle.

So, how do we fix this? Really, it can be quite simple, like as simple as all of us craft beer or wine or hard seltzer drinkers making sure we are always open-minded and looking for the experience of tasting to be a conversation and not some recitation of designated “correct” terms. We can make sure we never judge what anyone says they taste or smell in a drink, because, again, it’s all subjective, and when it comes to more formal circumstances like competitions and educational settings, we can take even the terms that might surprise us and find common threads and connections. As Dr. J mentioned, this should all be a collaborative process.

From there, those of us who work in beverage alcohol can find opportunities to open these discussions up, spotlight other cultures, and welcome all. Miroki cites the work of Beverly Crandon, who creates and hosts wine-pairing dinners with Caribbean and African cuisine, foods and cultures that are often left out of the too Eurocentric conversation. Miroki also mentions Ren Navarro of Beer. Diversity., who changed the curriculum of a beer history course she was teaching at the Niagara Winery Teaching College because of how Eurocentric and limited in scope it was.

Samer points to resources that speak to, include, and spotlight other cultures, and that take a fresh approach to teaching about things like style definitions by using terms that are more widely relatable and accessible, like Dom “Doochie” Cook’s book This Ain't the Beer That You're Used To: A Beginners Guide To Good Beer, and Em Sauter’s Pints and Panels.

While Em, for example, is an Advanced Cicerone and experienced beer judge, and Pints and Panels is a valuable educational resource and study guide for the Cicerone exam, there is nothing not accessible to all in the material (the fact of which is underlined by the fact that it’s all free!), and there’s even this tone of irreverence, whimsy, and fun to a lot of it, like the “beer and life” pairings. It reminds us that there’s a big world of Serious Information to know about beer—and wine and other drinks—but that it’s also beer, and is supposed to be fun, and is supposed to get you excited, and is supposed to welcome everyone. On the wine end of this, I have to recommend @freshcutgardenhose, the illustrations of somm and author Maryse Chevrier. Maryse draws the words of somms and wine critics in these charming, tongue-in-cheek, and 100% literal works—she is someone who loves wine and knows her shit, but is reminding, say, elitist wine snobs to calm tf down: this is all subjective, so much of this language is so personal or even kind of silly (“Worn leather boots in fresh soil, kicking up rooted bell peppers.”), and every wine is open to interpretation for every palate.

Beer Tarot!

This week, I pulled the Seven of Cups.

Cups is the sign of love, emotions, and relationships, and the Seven of Cups speaks to choices, opportunities, and the possibility of being disillusioned by wishful thinking or of confusing what you think you want with what you actually want. See how some of the things coming out of the cups are dazzling and lovely, and others are gross-o and wicked? This card’s got “be careful what you wish for” vibes. In short, don’t get distracted by shiny things when they might not be all that great for you or your life in the long run, and won’t bring you much happiness at all.

The Seven of Cups is a good sign, because it signals you are or are about to be facing all these new opportunities. Potential abounds. There are exciting new journeys and life upgrades ahead, but you’ve got to make sure you make the right choices for the right reasons. The higher-paying job offer might have dollar signs dancing before your eyes, but the one paying just a little less might be the one that lets you work from home when you want, or doesn’t have a toxic person in leadership, or gives you ample PTO, etc. What’s better for you, your mind, your wellness, your long-term happiness? Sometimes, the choices aren’t even that obvious, so you’ve got to really think about them and play out the paths they’d take you on in your head. If you make this decision now, how do you think it might affect where you are in five years?

Beyond this practical thinking and reasoning, don’t get too bogged down in just daydreaming about the possibilities. This card is also about actually acting, not just dreaming up, and not getting so distracted by whatever’s next that you abandon the path you’re already on, even if it’s working out well for you. Basically, make well-thought-out decisions, but also, live your life. If you choose the things that will fulfill you in the long run, you can stay the course and see them into fruition rather than quitting them halfway through to start another project you won’t care about finishing. Leave things that don’t serve you, stick to things that do, be considerate in your choices, and stay present in what you’re doing and where you are.

One thing you can daydream about is a decadent, well-made IPA—but only for a minute, then you gotta just get it and drink it, k? That’s what we’re talking about here. So, get Other Half’s DDH Double Citra Daydream.

This Week’s Boozy Media Rec

It’s no surprise to find Kate Bernot breaking news of an industry-shaping trend, and I found her recent story for The Washington Post fascinating. “Craft beer is polarizing: More drinkers want high ABV or none at all” examines consumers’ shift toward beer’s ABV edges. It takes one thing we now know well, which is that non-alcoholic craft beer is hot, and introduces the move for many consumers to prioritize getting more alcoholic bang for your buck—0.05% ABV IPAs or 12% imperial stouts or bust! Not only is this a need-to-know trend for breweries, distributors, beer writers, etc., but it also does that magical thing: reminding those in the craft beer industry world that it’s a small world, indeed, and much of what happens inside it does not translate to craft beer consumers. All we hear and talk about is how, for example, brewers don’t want to kick back with a TIPA at the end of the day, and seasoned Beer People want all things light and crisp and refreshing and easy-drinking. It helps to remember there’s another craft beer world outside the industry craft beer world.

Ex-BEER-ience of the Week

My ex-BEER-ience of the week should have been catching two powerhouses of brilliance, community, and inclusion, BierWax co-owner Yahaira Maestro and NYCBG executive director Ann Reilly, speak at the most recent Other Half Women’s Forum, but I—upon seeing a true shit show of train delays and redirects—took a pricey Uber to the wrong Other Half location and missed the whole thing. I also left my phone at home for the entire ordeal. In addition to being really upset to miss the forum, I took the sign from the universe that I had way too much on my plate last week because…wow what a dumb mistake.

Anyway, the Open Work Duivelsbeer I had at Grimm on Saturday is more than worthy of a spotlight, too, so I’m happy to give it. Grimm has resurrected the Duivelsbeer, a cousin of the lambic that’s spontaneously fermented and aged in oak, for the first time since the Belgian style pretty much fell off the map 20 years ago. I’m not a huge fan of sour beers (or I’d like to be, but my stomach cruelly says nope) but there’s something about a darker sour or wild ale I can and love to do. It’s a bit more like a nice red wine, with some sweeter, rounder dark fruit and malt notes tempering the acidic tartness and funk. Get it on draft or in bottles while you can!

Until next week, here’s Darby doing what I like to think is a smile(?) at said Grimm visit.